In Belarusian schools from the first grade, we were taught: “Belarus is the heart of Europe”. Our teachers meant, of course, the geographical position of the Republic of Belarus on the European continent. But the philosophical meaning of this phrase has long since taken on a cruel, humorous-sarcastic tone. Being “Europe’s last dictatorship” and the last European country with an authorised death penalty (the last recorded execution took place on December 17, 2022). It is hard to believe that this state could play the role of anyone’s heart.

To be less romantic and more accurate to the facts, I suggest you pay attention to the Amnesty International Report 2024/25, Belarus: “The authorities continued to crack down on all forms of public criticism and abused the justice system to penalize peaceful dissent. The suppression of independent media and civil society organizations escalated. Torture and other ill-treatment were endemic, and impunity prevailed. The enforced disappearance of prisoners was widely practised. The LGBTI community continued to face harassment… In October, the UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights situation in Belarus stated that the country’s engagement with the UN human rights system had “reached its lowest historical point.”

“Harassment” is the word international reports often use, but it barely grazes the reality of queer life in Belarus. Homosexuality has been legal since 1994, yet equality remains absent: there is no recognition of same-sex unions, no protection from hate crimes, no shield against discrimination. Instead, state policy cultivates stigma. Pride marches are banned, public mention of LGBTQ+ identity is denounced as “Western decadence” or “mental illness,” and a rainbow flag in Minsk can be enough to draw violence. The repression has only deepened. In 2024, the Ministry of Culture classified depictions of same-sex love or trans identity as “pornography,” lumped together with pedophilia and necrophilia, punishable by up to four years in prison. Lawmakers are now preparing a broad “anti-LGBT propaganda” bill, modeled closely on Russia’s legislation, which would criminalize any public affirmation of queer existence. Police raids, interrogations, and beatings have already become routine. And yet, the community endures. Underground drag shows, encrypted Telegram networks, and coded art exhibitions testify to a resilience that survives in the shadows. In Belarus today, to live openly as queer is not just identity but defiance, a fragile act of faith that one day Europe’s promises of dignity and equality will cross this border.

Introducing the Voices

To understand what it means to be queer in Belarus today, I spoke with five very different people: artists, migrants, activists, and those still living inside the country. Their stories illuminate the fractures of a society where visibility can be lethal, but silence is equally insufferable.

Sergey Shabohin and Gleb Kovalsky belong to a generation of Belarusian artists for whom art has always been inseparable from politics and personal experience. Sergey is a visual artist, curator, and editor of Kalektar.org, a portal dedicated to Belarusian contemporary art. Earlier, he created Art Aktivist, a project that explored the political dimension of artistic practice. Today, he lives openly as a gay man with his partner of eighteen years. Before his relocation to Poland, he kept his sexuality hidden. “Only later did I come out,” he told me. “Back then, the space for queer life in Belarus was almost nonexistent.” Through exhibitions, curatorial and editorial work, including projects at Minsk’s Gallery “Ў”(ü), which once hosted international figures like Tilda Swinton and Wolfgang Tillmans. Sergey helped bring feminist, queer, and politically engaged art into Belarus’s cultural discourse.

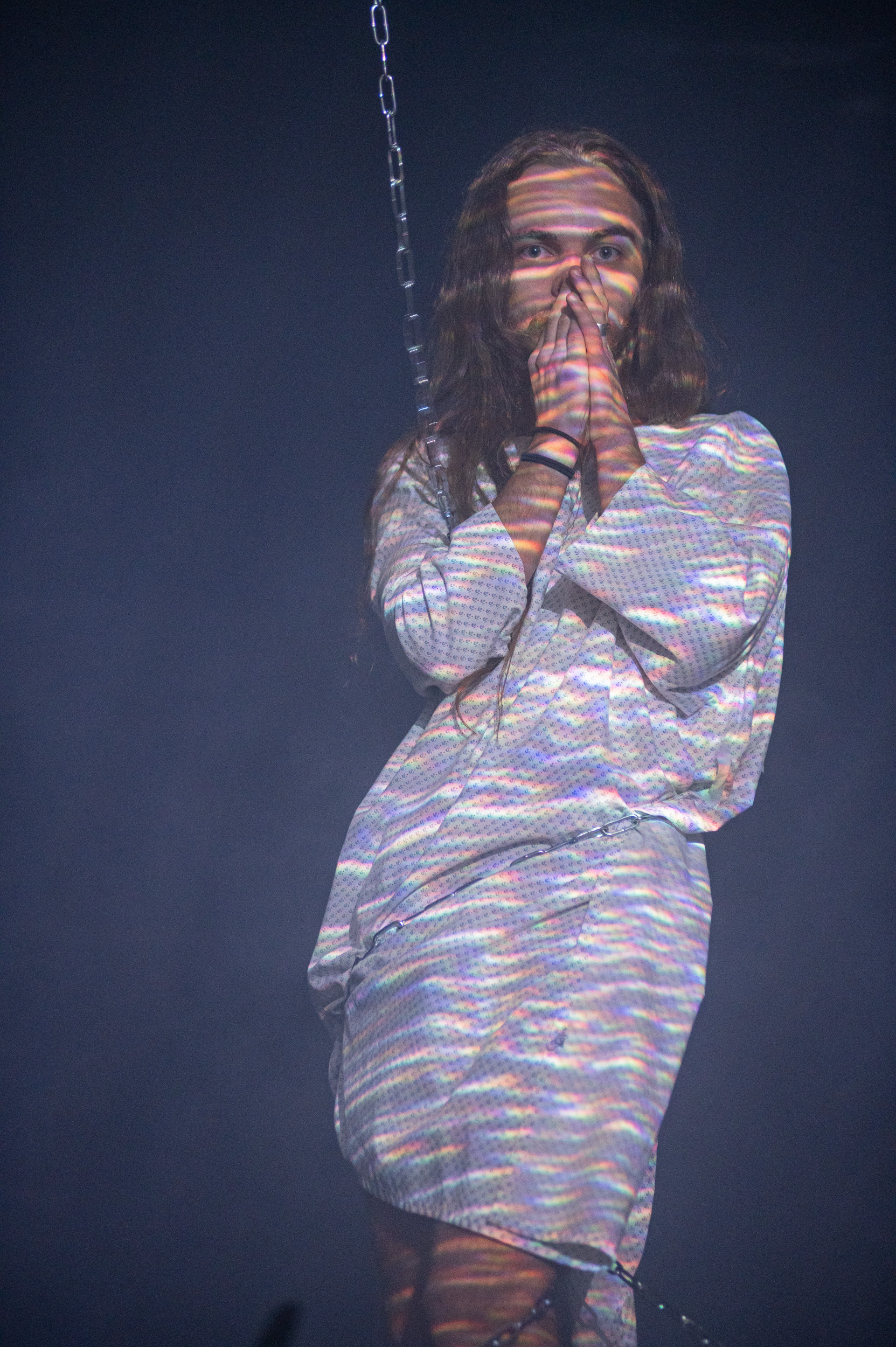

Gleb Kovalski © Siarhei Balai

Gleb’s path has been different, though no less intertwined with activism. For more than three years, they have lived in Berlin, studying at the University of the Arts. Their practice now centers on migration, displacement, and exile, often through performance and music. But before leaving, they lived a paradoxical double life: on one hand, organizing underground queer interventions and co-founding the legendary party series Petushnya, spaces of freedom for Minsk’s LGBTQ+ community; on the other, working inside the state propaganda machine, the Belarusian Television and Radio Company. “It was a performance of its own,” they said of those years. That performance ended abruptly in 2020, when they joined the wave of protests, both on the streets and through a strike within the broadcaster. Their reward was dismissal and threats; others were less fortunate. Colleagues faced prison terms like journalist Ksenia Lutsina, who spent four years behind bars for trying to build an alternative media channel.

Gleb Kovalski © Siarhei Balai

Pavel, or Pasha as he prefers, comes from Minsk. “I’m gay, a chef, sometimes a DJ,” he says with a laugh. His story, however, is marked by displacement: today he lives in Tel Aviv, after seeking asylum there. “I didn’t plan to leave,” he explains. “But in Belarus, I couldn’t imagine a future.”

They mocked me, beat me. They called my mother in. A Headmaster sat us down with a lecture: this is not normal. I ran straight home, locked myself in the toilet, and spent the night there. Because my mother was the scariest part—I was her shameful son. I was 14.

Lina is a bisexual cisgender woman, now based in Warsaw. She has been active as an illustrator within Belarusian civic initiatives and joined the protest movement rather than specifically queer activism. “For me, the struggle was one: democracy, freedom, dignity. Being bisexual is part of who I am, but in Belarus, you rarely have the luxury to separate one struggle from another.”

The last voice comes from an anonymous woman in Brest, who asked that no identifying details be shared for safety reasons. “I am a lesbian,” she wrote. “I still live here. That’s all I can say.” Her very silence is eloquent: in Belarus, sometimes survival means staying invisible.

Understanding the Situation

Let’s discover this landscape of overlapping fears. Some inherited from Soviet silence, others freshly engineered by a regime that thrives on paranoia. Everyday life for LGBTQ+ people unfolds in a continuum of risk, from whispered slurs on the street to outright state repression.

Sergey has observed the country’s queer reality from within and in exile, calling Belarus “a deeply patriarchal and homophobic society where even before 2020, living openly was too dangerous.” He and his partner confined their identity to a small circle of trusted friends. It wasn’t only fear of assault, though attacks and even murders have been documented, but also a cultural stigma so normalized it could masquerade as common sense. Parents urged them “not to show it off.” A state job for an openly gay man was unthinkable; dismissal was practically guaranteed. The insult was compounded when the government borrowed from Russia’s “anti-propaganda” playbook, lumping LGBTQ+ people, the child-free, and pedophiles into one toxic category, a grotesque sleight of hand that authorized new layers of repression.

For Gleb, once definitely visible in Minsk’s queer scene, the shift has been brutal. “What I did then, performances, parties, public art, would now mean prison, or death,” they said without hesitation. Since the regime’s purge of civil society in 2021, which wiped out some thousand NGOs, including every group working on LGBTQ+ rights, even documenting reality has become impossible. “There is no data anymore,” Gleb adds. “Only fear.” After five years of unrelenting repression, daily life in Belarus has collapsed into avoidance and silence. For queer Belarusians, it isn’t just fear, it is the constant knowledge of being hunted.

For Lina, the struggle starts at home. “First with internalized homophobia,” she says. “Then, with the weight of coming out to family and friends.” Her story mirrors that of a woman from Brest, who only began to accept herself after meeting her partner. In public, the two can sometimes pass as “just friends holding hands”, a fragile camouflage male couples can never claim. But even this cover is perilous. “In Russian-speaking countries, lesbian relationships are hypersexualized,” the woman explains. “There are always men eager to ‘show a real man’ and cure you. The risk of sexual violence is enormous.” She recalls Lukashenko’s remark that he pardons lesbianism as something women “choose” after disappointing men, a grotesque joke that, though it was never followed by legislation, marks queer lives as deviant.

For me, the struggle was one: democracy, freedom, dignity. Being bisexual is part of who I am, but in Belarus you rarely had the luxury to separate one struggle from another.

And then there is Pasha, whose initiation into visibility came inhumanely early. His coming-out was forced. A flirtatious exchange with another boy in school was exposed overnight. “The next day, the whole school knew. They mocked me, beat me. They called my mother in. A Headmaster sat us down with a lecture: this is not normal. I ran straight home, locked myself in the toilet, and spent the night there. Because my mother was the scariest part—I was her shameful son. I was 14.” Years later, the pattern repeated in a darker key. One night in 2020, after leaving a bar in Minsk with a date, he heard shouts behind him: homophobic slurs hurled by two large men in plain clothes. Then a blow to the head. He collapsed, his skull slammed against the asphalt until he blacked out. His date, whom he had said goodbye to a bit earlier, eventually returned and dragged him to a hospital. The diagnosis: a severe concussion, a smashed nose, after two operations, the doctors said it couldn’t be repaired.

What followed revealed as much as the attack itself. Because his injuries were classified as “serious,” the case became automatic. It turned out the beating had happened in full view of a surveillance camera. The men were quickly identified as law enforcement officers. During the investigation, Pasha was under tremendous pressure, and in court, the attackers justified their actions by Pasha’s orientation. The trial produced a farce of justice: one was released without penalty, the other received a minor administrative sanction. “For almost killing someone,” Pasha says with a bitter laugh. Recovery took six months. His story is not an exception but a parable. In Belarus, the line between random violence and state violence has blurred so completely that queer existence itself feels like an ongoing interrogation.

After the Storm

The 2020 protests marked a turning point and not for the better. Lina notes that queer rights were largely absent from the agenda: “Until recently, this topic was silenced, as if it didn’t matter. But if we want democracy in Belarus, we must speak about LGBTQ+.”

Sergey links the deterioration to the state’s post-protest crackdown and Russia’s influence, including Belarus adopting a near-verbatim version of Russia’s “gay propaganda” law. Where tolerance once existed, it was crushed: feminism, LGBTQ+ identity, and even childfree choices became stigmatized or criminalized. As recently as 2018, small queer festivals and politically tinged exhibitions were possible, albeit closed; yet bureaucratic pressure from fire inspectors, sanitary commissions, and ideological authorities already foreshadowed the current rollback.

Gleb recounts new forms of repression, such as “fake dates”: police create profiles on Grindr or Hornet, arrange meetings, then detain and abuse participants psychologically or physically. Trans people are especially vulnerable; Gleb cites Diana Gordan, a trans woman detained and beaten for hours during a night raid, threatened with sexualized violence. These arrests often occur without charges or protocols, serving purely as demonstrations of power and humiliation.

Mass violence became normalized. Torture, rape, and killings went unpunished. Even nightclubs, once “islands of respite,” are now heavily monitored. Any hint of queer themes on stage can result in bans, blacklisting, or criminal prosecution. Political subtexts in art, previously spaces for subtle protest, are now fully suppressed. Administrative and criminal codes, including Articles 24.23, 342, and 368 [Article 24.23 – Administrative Code: Violating Procedures for Organizing or Holding Mass Events; Article 342 – Criminal Code: Organization and Preparation of Acts Seriously Disrupting Public Order; Article 368 – Criminal Code: Insulting the President of the Republic of Belarus], enforce this new order.

By August 2025, possibilities for LGBTQ+ activism inside Belarus remain minimal and extremely risky. Proposed laws modeled on Russia’s anti-LGBTQ+ measures further limit advocacy and visibility. International condemnation, from the UN or EU, has had little effect. Activism inside Belarus has largely gone underground or moved abroad, where exiled Belarusian activists can organize, campaign, and collaborate with international NGOs, providing critical informational and moral support to those still inside. Bureaucracy and limited resources remain major obstacles.

Until recently, this topic was silenced, as if it didn’t matter. But if we want democracy in Belarus, we must speak about LGBTQ+.

For many, leaving Belarus is both life-saving and traumatizing. Sergey, living in Poland since 2016, has built a new life producing theater and running Gray Mandorla Studio. In Poznan, he and his partner can live openly within a welcoming queer community, and he still hopes for eventual legal recognition despite occasional homophobia.

Gleb emphasizes that forced migration itself is a form of repression. Since 2020, between 300,000 and 1 million people have fled Belarus. Many of them are LGBTQ+. Adapting to a new country, language, and social context brings severe psychological stress. Temporary refugee shelters in Germany or the Netherlands may be physically safer but often isolating, or even hostile, with reports of suicides and extreme vulnerability among queer residents. Emigration saves lives but deepens trauma: loss of homeland, community, and cultural identity becomes a daily reality. For LGBTQ+ Belarusians, exile is a paradox, freedom from immediate threats exists alongside enduring psychological, social, and cultural hardship.

Belarus calls itself the heart of Europe, but for its queer citizens, the organ feels more like a clenched fist. And yet hearts have a way of betraying their owners, they keep beating, even in exile, underground, or silenced. Whether in Warsaw, Poznan, Berlin, Tel Aviv, or still in Brest, they sketch out a future Belarus refuses to imagine. Their existence is already a politics, their survival already a resistance. In that persistence lies a lesson for the world: dignity cannot be legislated away, and humanity cannot be erased by fear. One day, perhaps, the phrase “the heart of Europe” will shed its irony. Until then, the beat persistently comes from its underground, waiting for someone to finally hear it.