As a queer activist from Türkiye, I have spent years observing both the struggles and resilience of my community. Today, I could talk about a draft law seeking to criminalize gender nonconformity or the recent detention of nearly 50 LGBT+ activists. But in a time when so many feel hopeless, I want to share something beautiful about queer culture in my country. So here is the story of Lubunca, a coded language that has endured for centuries against all odds.

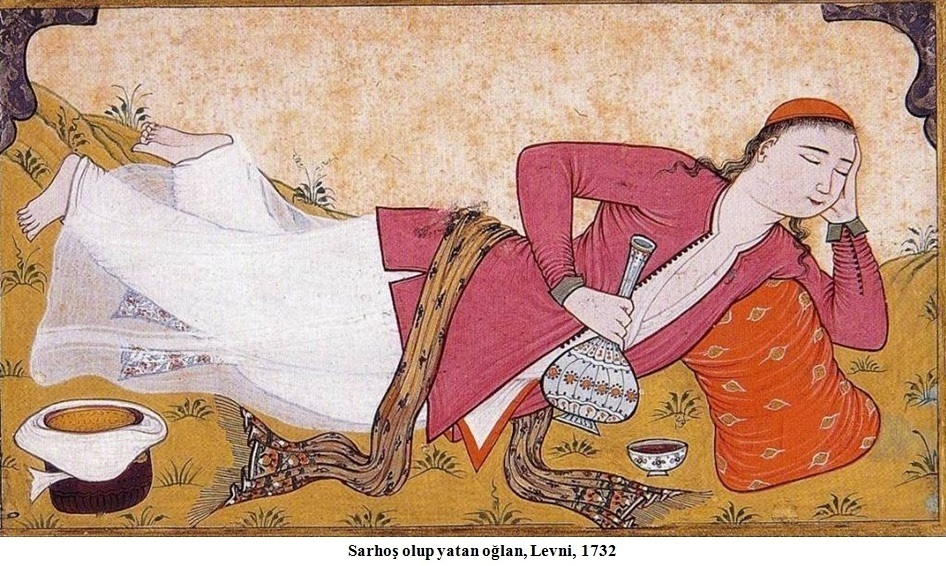

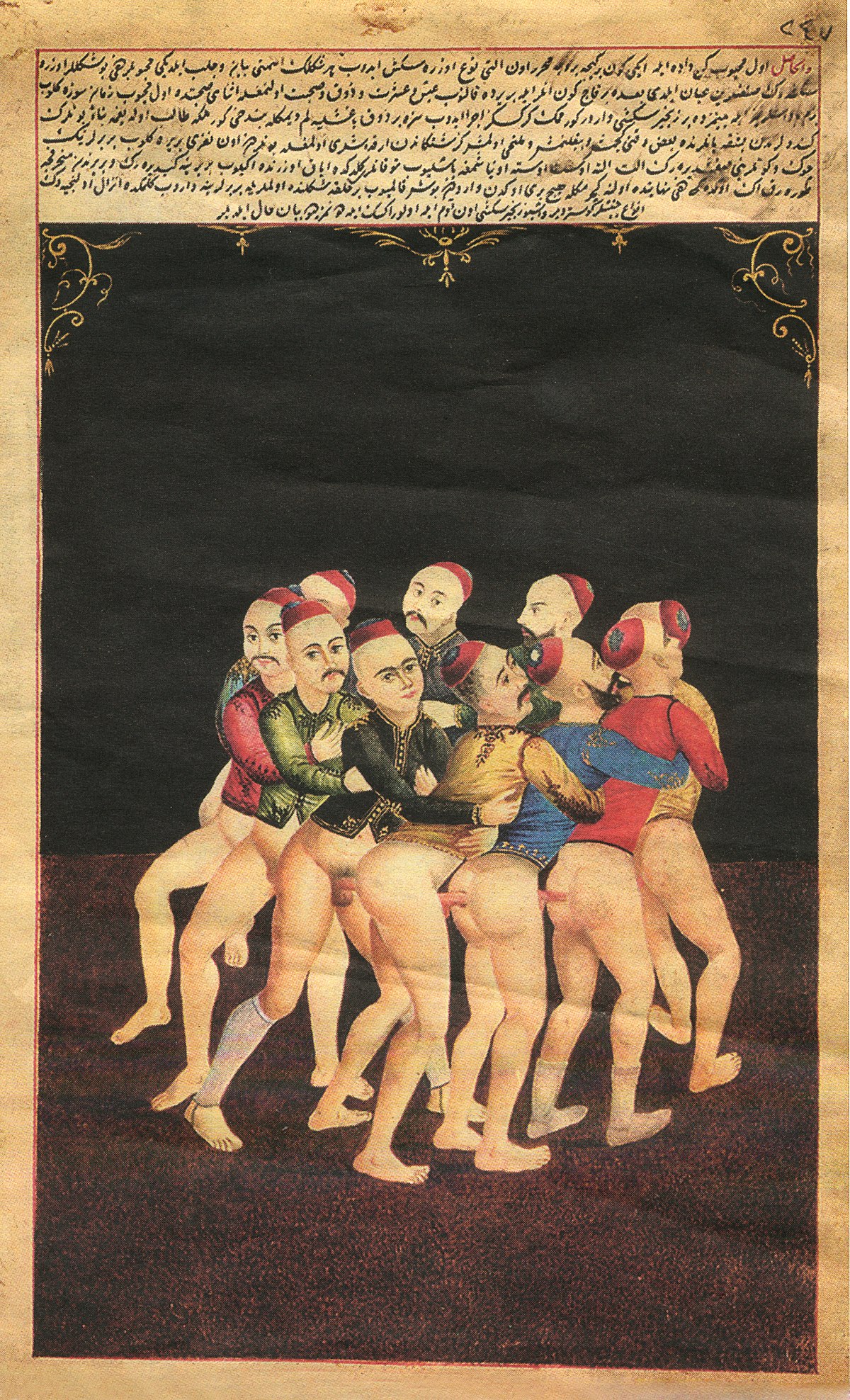

Simply put, Lubunca is a secret language created by trans women and gay men living in the Ottoman Empire. Given the empire’s vast and diverse structure, trans and gay individuals—many of whom spoke different native languages—struggled to find a common space. To bridge this gap, they developed a way to recognize one another on the streets and communicate safely at a basic level. While the exact origins remain unknown, historical records trace Lubunca back to the 17th century. It was commonly used in traditional Ottoman bathhouses, coffeehouses, and palace entertainments. In particular, Zennes—male dancers who performed in women’s clothing—integrated Lubunca into their performances. It is likely that the Ottoman aristocracy, after hearing the language during these entertainments, began using some Lubunca words themselves. However, documentation on its everyday use remains quite limited.

While the exact origins remain unknown, historical records trace Lubunca back to the 17th century.

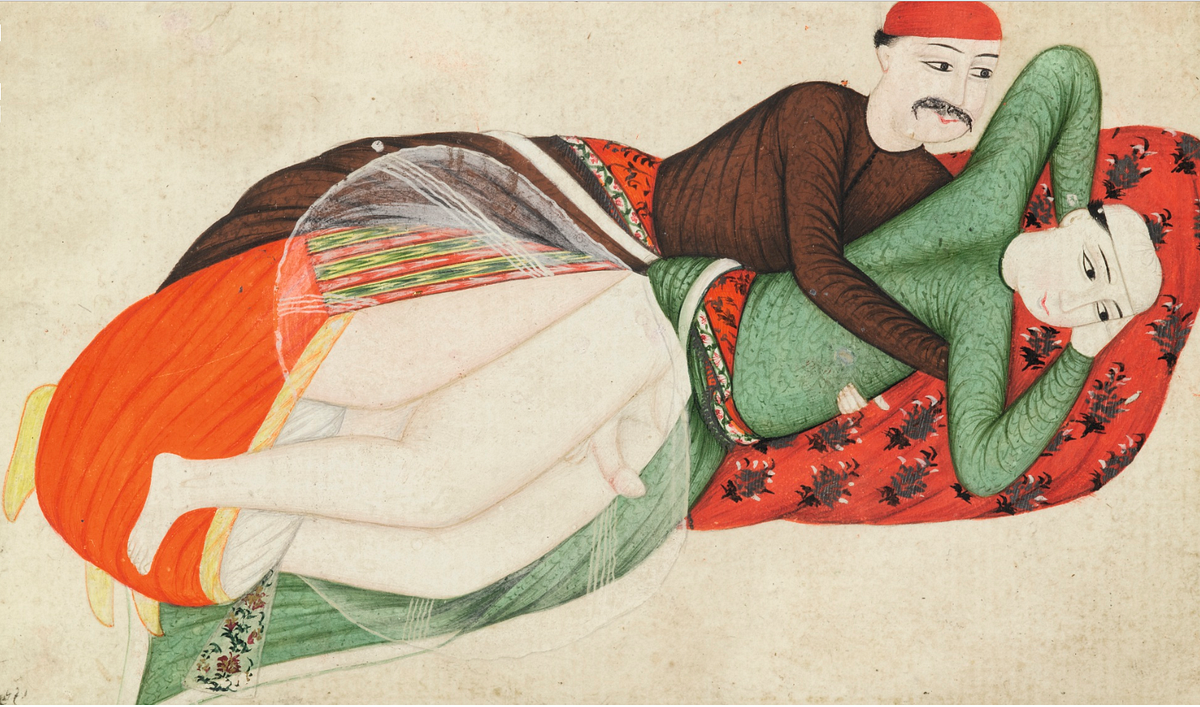

Despite the Ottoman Empire’s relative tolerance towards homosexuality—it was the second nation to decriminalize it in 1858—not all gay and trans individuals were as fortunate as those in the palaces. Many were indeed forced into sex work to make a living, and lived together in overcrowded ghettos. These areas were also home to other marginalized minorities, creating a diverse yet precarious environment shaped by economic hardship, social exclusion, and frequent raids by authorities. Within this setting, queer people not only faced social discrimination but also systemic violence, leaving them in a constant state of fear and precarity. To communicate secretly without being understood by neighbors, clients, or law enforcement, trans and gay sex workers began borrowing words from the languages spoken around them—Romani, Greek, Arabic, Bulgarian, Armenian, Persian, Kurdish, and others—ultimately giving rise to Lubunca. They adopted the Romani word lubni/lubun, meaning “prostitute,” as a way to describe themselves. In doing so, they created a new umbrella term that remains in use within the community today to refer to all LGBT+ individuals in Türkiye.

The Romani word lubni/lubun, meaning ‘prostitute,’ was adopted as a way to describe themselves.

The idea behind Lubunca was simple: imagine a five-word sentence, with each word borrowed from a different language. Anyone unfamiliar with all five languages would struggle to understand their meaning. To make it even more difficult, the Lubuns twisted the meanings of some words—for example, saying “whale” instead of “soldier”—making the message even harder to understand. However, this did not require the Lubuns to learn an entirely new language. They only needed to memorize a few hundred borrowed words, allowing them to recognize each other and communicate safely, even without a shared mother tongue. That said, Lubunca wasn’t designed for casual conversations like “I ate potatoes this morning.” Instead, it was meant for urgent statements such as “This man is a psychopath,” “This house is dangerous,” “The police are coming,” “You need to run,” or even “Did you just fart?” It also provided a way to talk about mental and sexual health, sexual performance, penis size, beauty, and financial matters. In a way, it allowed them to gossip openly in front of others—perfectly fulfilling all the fundamental communication needs of a Lubun.

From the book Sawaqub al-Manaquib, 1691

A Sodomite Disgraced by Khayr Allah Khayri Jawush Zadah, 1721

Tuhfet Ül-Mülk (The Realm’s Gift) by Shaykh Muhammad Ibn Mustafa Al-Misri, 1773

Lubunca in Modern Türkiye

By the early 20th century, the Ottoman Empire had collapsed, paving the way for the newly established Republic of Türkiye. However, the challenges faced by the LGBT+ community did not disappear. As the young republic struggled with military coups, the weight of these coup regimes fell particularly heavily on LGBT+ individuals, especially trans women sex workers. In the 1980s, the government forcibly removed them from their ghettos and relocated them to various parts of Türkiye. During this period, their need for a covert language to communicate without being understood by abusive police officers propelled Lubunca into its golden age. Holding on to it even more tightly, trans women sex workers expanded their vocabulary and shaped it into its modern form. By this time, Lubunca had spread across the whole LGBT+ community, though trans women remained its most fluent speakers. Once a hidden code used in traditional bathhouses, Lubunca had now also emerged as a secret language spoken in clubs, discos, and bars.

Trans women sex workers expanded its vocabulary and shaped it into its modern form.

After the 1990s, Lubunca evolved into a playful tool for humor and satire, allowing LGBT+ people to mock societal norms while gradually gaining popularity in the media. Over time, LGBT+ actors, singers, and comedians began slipping Lubunca words into television shows. One of my most vivid memories is watching Huysuz Virjin (Grumpy Virgin), a famous drag queen, light up the screen with her sharp wit and flamboyant humor. She often used Lubunca to tease the audience, and everyone I knew—including my family—watched her. Although such TV programs declined with Türkiye’s increasing authoritarianism, it didn’t take long for Lubunca to find its place on social media. Today, Lubunca can be learned through YouTube videos or personal blogs, and despite the ongoing pressure, its popularity continues to grow. While this visibility has been a positive step for LGBT+ representation, it has also sparked debates within the community. Some argue that Lubunca’s widespread use violates the safe spaces of trans women sex workers, who originally created and relied on it for protection. In response, they have developed new wordplays and modifications to safeguard the language once again.

Note: One of the most significant ghettos mentioned was perhaps Istanbul’s Beyoğlu district. The changes that took place in this area greatly shaped the language. For instance, with the construction of the Italian Catholic Church, some Italian and Latin words found their way into Lubunca, while some Spanish and Hebrew words were introduced through the Jewish diaspora that had fled Spain. It is also believed that some French words entered Lubunca after the relocation of the French embassy to this area. Here are three of them, along with their meanings:

Pissoire / Pişar: To urinate

La Bouche / Lapuş: To kiss

Lavage / Lavaj: Enema

Today, nearly 400 years later, Lubunca remains an inseparable part of the LGBT+ struggle in Türkiye. LGBT+ organizations actively teach Lubunca and use it as a tool of resistance against oppression. A recent notable example is the Queer Film Festival (KuirFest), which, despite a government ban, has continued for the past two years under the name “Küründen Online” (Pretend to be online). Since authorities do not understand the meaning of the Lubunca word “Küründen,” they assume the festival is actually taking place online and refrain from intervening. Meanwhile, those who do understand the meaning share it with others, further strengthening solidarity. This means that not every LGBT+ person in Türkiye knows Lubunca, but one of the first things they do when joining the community is learn it. In fact, they have to—because, in some cases, their survival still depends on it.

A world beyond gender roles, where everyone feels equal and included.

Considering all this, Lubunca is more than just a coded language; it is a cultural space that brings people together and gives them a sense of belonging. It creates a hidden world where those who recognize it exchange greetings—a world beyond gender roles, where everyone feels equal and included.

The learned are all enamored of boys,

Not one remains who female love enjoys.