The Brussels-based European Pride Organizers Association (EPOA) is a network that brings together Pride organizers from across the continent — stretching from Poland to the United Kingdom, from Turkey to Luxembourg. While its primary mission is to facilitate the exchange of knowledge, resources, and solidarity among its members, the EPOA also acts as a political voice at the EU level, advocating for the rights of LGBTIQ+ people and coordinating the EuroPride, the well-established Pan-European Pride event and meeting point for the wider queer community, hosted by a different city each year.

However, the seemingly inevitable rise of right-wing populism across Europe, spreading anti-LGBT+ narratives and hate speech, and the ensuing targeted violence against queer individuals, particularly trans people, have put further pressure on the fundamentally festive organization. In the wake of this year’s EuroPride, which took place in Lisbon late June, queer.lu spoke with EPOA president Patrick Orth about the declining state of LGBTIQ+ rights across Europe, Pride bans, and the urgent need for collective resistance—but also about something perhaps even more vital: hope.

queer.lu: ILGA Europe is one of Europe’s leading umbrella organizations on queer rights. In their most recent report, published alongside the Rainbow Map, Advocacy Director Katrin Hugendubel stated that we are witnessing “a coordinated global backlash aimed at erasing LGBTI rights”. How does the EPOA assess the current situation in Europe?

Patrick Orth: What we’re seeing is an attack on freedom of speech and freedom of assembly. And it shouldn’t only concern queer people; it should concern everyone living in a civil society when a government starts taking away basic human rights. I believe the European Union should be more concerned that these rights are under attack within its own borders. It shocks me how silent Europe, or more precisely the European Commission, is at the moment. They’ve said some really nice things, but no real action has followed. I appreciate that some members of Parliament tried to freeze funding to Hungary. And we’ve seen that this approach can work — remember the LGBT-free zones in Poland. When the EU froze funding to Poland, those zones suddenly disappeared. I think that’s the very least the EU should do to show its support.

Looking at the ILGA report itself, what shocked me most wasn’t the countries at the bottom of the ranking; they’ve more or less always been there. For me, one of the most alarming things is that the United Kingdom is no longer in the green zone. It dropped to the orange zone because of the backlash against trans rights. We mustn’t forget that 10 or 15 years ago, the UK was leading the Rainbow Map. Now it’s falling lower and lower every year. The rights of trans people in the UK are now endangered by law. Their Supreme Court ruled that a woman is only a woman if she was assigned female at birth. To me, that’s even more shocking than seeing a dictatorship like Russia still denying queer rights altogether.

You touched upon the situation in Hungary. With Pride events being banned in Hungary, how have national organizers and EPOA responded to the increasing political pressure?

We immediately met with the activists working on the ground and asked how we could support them — what do you need from us? The two biggest things they need are visibility and money. That’s true for almost everyone: what they need most is visibility, and to achieve that, they often need money. So what we’re trying to do at this point is reach out to our members and ask if they can donate money to Budapest Pride to support them. The overall situation is that many companies, especially those based in the United States, are cutting their support. Many Prides in Eastern Europe used to receive backing from US embassies, but that support has now been cut entirely.

We’re also working to raise awareness, engage with politicians, and mobilize people to go to Budapest on June 28, despite the ban imposed by Orbán and all the threats he’s making. We’ve also connected Budapest Pride with other Prides in our network that have experience organizing under similar circumstances. Some of that experience goes quite a way back, to be fair, but there’s still a lot of valuable knowledge within the EPOA network.

What is the current legal status of the Pride ban in Hungary? Is it lawful to ban Pride events? Are there concerns that similar actions could be taken in other European countries? And what does the future hold for the basic right to protest?

This is an attack on basic rights such as freedom of speech and freedom of assembly. I think the European Union cannot allow this ban to stand. Not only to show support for queer communities in Hungary, but also to make it very clear that it is not up to the state to decide what people are allowed to demonstrate for.

I’m very concerned that if the EU does not take a stand here, other countries may follow, because they’ll see that they can basically do whatever they want. When we look, for example, at Bulgaria or other countries within the European Union that are shifting further to the right, if they see that Hungary is allowed to do what it’s doing right now, they might take it as a signal that they can do the same. This law is so clearly unlawful. It goes against everything we’ve agreed on as a Union, and I simply cannot believe it will stand.

Hungary has received significant attention for its continued legislative attacks on queer rights. However, EU member states like Romania, Poland, and, as you now mentioned, Bulgaria currently rank even lower on ILGA-Europe’s Rainbow Map. How do you manage these challenges and risks as Pride organizers?

We’re basically doing the same as we do in other countries, but the devastating part is that there isn’t just one crisis we have to focus on, there are many. And we’re working to make these crises visible. Take Bulgaria, for example. The country is on the brink of going down a similar path as Hungary. When I spoke with activists there, they told me they had never been very visible to begin with, because queer people in Bulgaria never had many rights. There’s no anti-discrimination law, no protections, so there’s very little that can even be taken away.

When we turned the spotlight to Ukraine after the full-scale invasion began, we were able to raise over €100,000 for our members there. At that time, and still now, what they needed most was money: to rebuild, to ensure safety for volunteers, and to support the people coming to them. I hope we can continue putting the spotlight where it’s needed, especially in Eastern Europe. After Belgrade 2022, I really hope we can bring EuroPride back to the region, because it’s one of the largest human rights events in Europe dedicated to queer people.

I think we can’t underestimate the power of a strong network. When someone is facing a problem, they know there’s likely another member who has faced something similar and found a solution. That kind of immediate access, just picking up the phone, writing in the WhatsApp group, or reaching out directly, is incredibly valuable. That’s what makes this network work. For instance, Prides in Eastern Europe have a long history of being targeted by hooligans and Nazis. I remember one year in Prague, people marched at the front with giant angel wings. When the Nazis were standing along the route, these “angels” blocked their view so that participants could feel safer. These kinds of creative, community-based responses are what we learn from and carry forward. That’s the real power of the network — people connecting, meeting, sharing experiences, and finding solutions together. I honestly believe that’s the most meaningful thing we do. It’s even bigger than EuroPride, in my opinion.

Outside the EU, we’ve seen increasing attacks on queer rights in countries like Russia, Azerbaijan, and Turkey – all of which received the lowest scores in ILGA-Europe’s rankings. How does EPOA monitor and engage with developments in these countries?

We have no members in Russia. We have no members in Azerbaijan and we also never had one. We do have one member in Turkey, which is a student organization. The situation in Russia and Azerbaijan is really out of our hands, because we depend on what people on the ground tell us. And if there’s no one we’re connected to, then it’s hard to know what’s really happening. Of course, it’s extremely concerning — absolutely devastating. But without members there, we can’t properly assess the situation.

When it comes to Turkey, I know my colleague Isabel, who is our human rights coordinator, has been in touch with our members there. We’ve had meetings and tried to get a sense of what’s going on. And the situation is very different from Hungary. Because in Hungary, the attack is directly on Pride. What’s happening in Turkey right now is on a completely different level — devastating, because it attacks every citizen in the country. It attacks every kind of freedom of speech and every kind of freedom of assembly. When political opponents are being imprisoned simply because they’re inconvenient for those in power, that’s a very different kind of crisis.

Just a few days ago, I got an email from Turkey listing ways we could help. And we will do everything we can. We’re going to speak up about it at the upcoming human rights conference in Europe, and we’re giving them a platform, so they can speak directly to others in the movement. We’re also trying to connect them with Prides happening across Europe, so they can have visibility, be on stage, and share what’s happening. That’s what we can do, and that’s what we’re doing.

Have you noticed common patterns in how these governments are targeting Pride events and queer communities? And what have you seen in terms of resistance — how are local communities fighting back?

It mostly starts with banning the topic from being discussed in schools. That’s where it always starts and it’s always done under the label of protecting children. People want to protect children. I mean, I want to protect children as well, that’s not a bad thing. But what they’re doing is using that to frame queer people as a danger to children. And this is happening everywhere. That’s also how things started in Hungary under the excuse of child protection. What they’re really trying to do is decrease the visibility of queer people.

Right now, the United States is doing this in a very remarkable way. They are trying to erase queer history. They are trying to erase trans people — basically saying they don’t exist, even though we all know they do. We see them. We know they are here. But still, they are trying to pretend otherwise. This is the pattern, I would say — trying to take away visibility. That’s what’s happening everywhere. And the first ones in line — the first ones targeted by politicians — are trans people. Trans people are always the first ones to face backlash.

How has the meaning of Pride evolved over the past few years, especially in the current political climate?

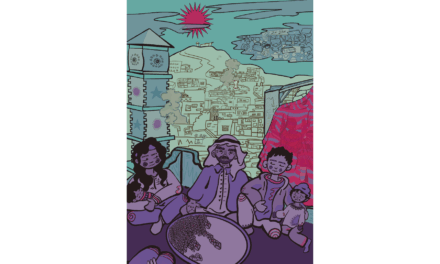

Over the last years, we can clearly see that the number of Pride events is rising everywhere. Attendance is also increasing in many cities. And that shows there’s a need for it. People wouldn’t go if they didn’t think it was worth going. Pride is still a story of success. Just look at Germany, for example. Last year, they adopted a self-determination law — meaning people can assign their own gender and name. A huge success. And that never would have happened without the pressure from the ground. The year before, Greece achieved equal marriage and not just that, but the full package: surrogacy, adoption, everything. And again, this happened because of the pressure from the streets. I’ll say it again: we will demonstrate on the 28th of June in Budapest, despite the unlawful ban by Viktor Orbán. Because you cannot ban Pride. It’s a basic right.

And what we’re seeing now in politics, but also in civil society, is this desire to go back to a so-called “cosy” past. A time when things that challenged their worldview could be ignored. Pride is more important than ever. They are banning Pride because they know how powerful it is. They know what it gives to people — the courage to go out into the streets, to be themselves, to meet others, and to feel part of a community rather than an outsider. And because it shows other people that there is nothing they need to be afraid of when they are together. I think this is why it’s more important than ever to visit your local Prides, to come together. To also find a friend or an individual to carry on for the rest of the year, to enjoy, have a good time, and recharge. Because in your daily life, you’re probably not always surrounded by uplifting queers. But Pride gives you that. And I really believe it has a powerful impact in every possible way.

Thank you for this insightful interview, Patrick Orth.