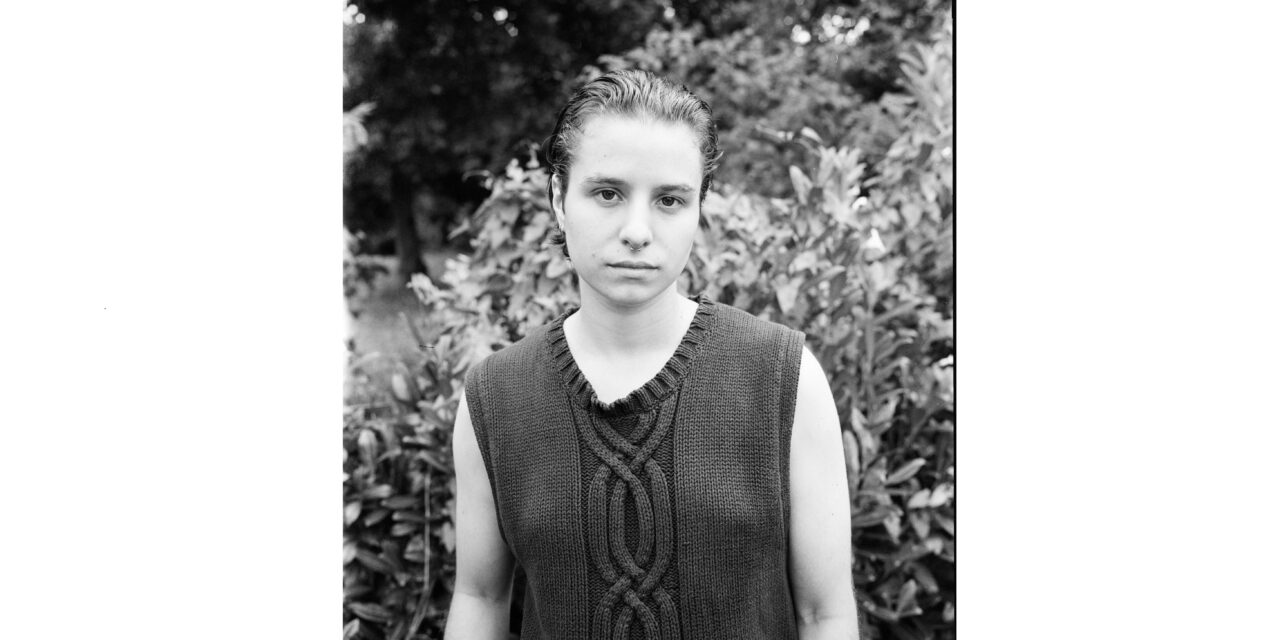

In May 2024, the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) published the results of a survey on the wellbeing of LGBTIQ+ residents. Respondents from Luxembourg revealed that 68% of them suffered from bullying, ridicule, teasing, insults and/or threats in school due to their queer identity. This is more than two out of three LGBTIQ+ people who faced such mistreatment. While these figures represent experiences from various age groups and might not mirror recent trends accurately, FRA specifically asked current students about their experiences. Nearly half (44%) of the respondents reported still hiding their identities in school. Olivia, a high school student, was not surprised by this. “I am one of those people. I am scared to tell people at school”, she admits.

Preferring to Keep Their Queerness Private

Now in her final year of high school at an international school, Olivia moved with her family from the U.S. to Luxembourg at age eleven. She speaks with clarity about her mental health journey as a queer student and explains that she has been hesitant to reveal her queer identity at school due to past experiences. Three years ago, Olivia was a victim of bullying. “For a couple of years, I got called an insult which then became a nickname,” Olivia recounts, “the insult referred to my sexuality and to my appearance. It got used by a lot of people in my school and specifically by that one person as they were in a lot of my classes”. Olivia explains that she felt uncomfortable at all times in school. While the bullying has died down, her bully remains at her school and still shares some classes with her. “I have to live with the knowledge that ‘you probably don’t remember this whatsoever, but it affected a large part of who I am’.”

Olivia did not tell anyone about this bullying until this summer when she opened up about it to her parents and later on her best friend. Back when it happened, “I tried to laugh it off and tried to become part of the joke,” she explains. “I didn’t seek help because I just wanted to shove it away. I didn’t want to talk to anybody about it. I didn’t want to acknowledge it”. Looking back, Olivia realizes that her mental health made her feel as though she somehow deserved the treatment. In order to protect herself, she started limiting her self-expression. “I try to blend in now, to avoid all of that attention”, she shares.

This has changed, however, since Olivia has gotten more support for her mental health through therapy. “Getting support outside of school has helped a lot. Personally, I initially didn’t feel comfortable seeking help where the incident happened.” After having gone to therapy, she says she now recognizes the value of in-school support as resources at school know the specificities of how your school works and can support you on an even more concrete level within your journey. Olivia knows that “going through school is already difficult enough. If you have someone there for you, it is much easier than going through it alone”.

Queer and neurodivergent

Bellamy, who graduated last year from a public secondary school in Luxembourg City, is not surprised by the statistics showing that nearly half of the students hide their queerness in high school. After a gap year focused on political activism, Bellamy is now starting a Bachelor’s degree in Natural Sciences abroad. “There is so much bullying in schools, even aside from queer identities,” they explain, adding that visibly queer people often can become an “easy target”. According to a 2022 survey, an average of six students per day and per high school seek help from SePAS (Service psycho-social et d’accompagnement scolaires), the mental health support service in public secondary school. Bullying ranked fourth among reasons for seeking help, following stress, depression and anxiety.

While their experience has been quite different from Olivia’s, Bellamy’s story was also fraught with difficulty. “I struggled to fit in, even in primary school,” they recall, “I was 10 or 11 when I first had feelings for a girl and I didn’t understand this back then”. Bellamy describes themselves as an insecure child. “I also didn’t fit into this gender binary and it confused me. I didn’t have any words to understand or talk about my experience. I kept wondering, why does everyone manage to fit into these expectations and I don’t?” Their family was mostly oblivious to queer identities and education about queer identities. They consequently felt left alone with figuring out their sexuality and gender.

In addition to their queer identity, Bellamy is neurodivergent. Neurodiversity refers to atypical brain development, which includes conditions like autism, dyslexia and ADHD. As their gender and sexuality differed from those around them, they started to “mirror” their surroundings in order to cope with expectations from close ones and also in order to find friends. Now, they know that this was a very common response for neurodivergent people in an environment which does not understand or accommodate neurodivergent children and youth. “People would ask ‘Oh, who are you imitating now?’ and ‘Why Can’t you just be yourself?’, but I honestly didn’t know how,” they say. Such comments were hurtful and confusing to Bellamy. They stayed largely friendless throughout these years with the exception of one friend, who remains their best friend today, and only found their social circle in their last years of high school.

Bellamy has been aware of the SePAS – “but it is like giving a book to someone who doesn’t know how to read,” explains Bellamy about their struggle. They first had to understand what was going on before they realized that these resources could have helped. “I didn’t have the words to explain myself.” Bellamy highlights language and thus education as key issues for them. “When you don’t have the words, you don’t have the means to understand your feelings, yourself but also the world around you.” After the added mental strain of the COVID-19 pandemic, Bellamy started struggling with depression. “At this point, the support from my family and SePAS were not enough anymore – and I needed to get therapy.” They are very thankful that their family supported them going to therapy and throughout their mental health journey.

Queer Education, In and Outside of School

Bellamy found a first sense of community in late secondary school. Namely, after the 2016 U.S. electoral race between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, Bellamy started to get interested in politics and to educate themselves through social media and news. As they read up on politics on their own, the student first came across the word nonbinary. Meeting other non-binary students solidified Bellamy’s understanding of their identity. However, they regret the lack of queer education in Luxembourgish schools. “We had one class in English that covered queer topics, but I missed it because I was sick”, they note.

In Bellamy’s biology class, intersex variations were on the school curriculum, but only as a named case without contextualization. “The word ‘intersex’ actually never dropped and we talked about it in the context of genetic disorders and mutations. It was simply on a list with trisomy 21.” As a genderqueer person themselves, Bellamy regrets that gender and sex were never explained as a spectrum and genderqueeress was presented as “a sexual anomaly”. They even reached out to their teacher and asked if they could talk about trans people in this context. “My teacher replied that we would talk about it next week and then, the week later, we actually talked about genetic mutations. He apparently had no clue what trans even means”. Bellamy’s experience is somewhat similar to that of most Luxembourgish LGBTIQ+ people as two out of three (66%) noted in the FRA survey that their education in Luxembourg never addressed LGBTIQ+ issues. It is clear for Bellamy that “this is a clear failure of the education system”.

High schools as safer spaces?

35% of LGBTIQ+ students noted in the FRA survey that someone in school often or always supported, defended or protected their rights as an LGBTIQ+ person. Even though Olivia and Bellamy speak of their challenges as queer high schoolers, this pattern is also reflected in the experiences of the two interviewed students.

Olivia even has become part of the people who actively support LGBTIQ+ people in their school. She joined the school’s Diversity, Inclusion, Equity and Justice Committee. The committee is composed of around 50 students, teachers and parents and aims to create a safer environment through events about mental health and Pride activities. “We also have a gay-straight alliance at my school,” says Olivia proudly, even though she is not part of the club herself and quickly notes that “it is quite small… because people are a little scared to go. You know, it’s high school”. One initiative which particularly touched Olivia was that her school hung up rainbow flags stating “you belong here” in the hallways. “Even though I don’t openly share my queer identity, these small things make me feel more welcomed in the space. It makes a big difference for me.”

Openly queer school staff has also left an impression on both students. Bellamy speaks of a queer history teacher who introduced himself as gay on the first day of classes and a surveillant*e, a substitute teacher, who wore rainbow accessories, such as earrings, t-shirts or socks, every day. “It just made me happy to see them and to see that there were also no confrontations about it.” Even though there are still many challenges for genderqueer people, Bellamy’s high school now also has a gender-neutral locker room for their gym class. In their last year, Bellamy also started to advocate for gender-neutral bathrooms on campus, but without success. In an email interview, the education ministry noted that they have been lobbying at eight different high schools, which soon built new buildings, to include gender-neutral bathrooms.

Systemic issues

Fortuna is an éducatrice graduée, a graduated youth worker. She worked as a surveillante and, later on, in a SePAS team at two different public high schools in Luxembourg. At SePAS, she was responsible for helping students with stress management and future planning and also worked on some awareness campaigns, notably one dedicated to people with disabilities. Fortuna understands why students might not feel comfortable with the SePAS resources.

“To be fully honest, I was the only young person without a partner in the office. Even I felt unsure about how comfortable I would feel within my team,” explains Fortuna, “and with teachers too. I would say that most teachers have rather traditional views. I heard from students of cases where a teacher said ‘are you gay?’ in a derogatory manner”. While there is continued education for school staff about queer topics, these are not mandatory. Beginning 2025, the Centre psychosocial et d’accompagnement scolaires will also publish a guide for Luxembourgish school staff on how to support trans students, according to the education ministry. Resources thus exist and keep being created, but the question remains if school staff make use of them.

For Fortuna, it was important to “make sure to visibly show that I am at least an ally” as she always included the rainbow colors somewhere in her outfit. During the breaks, Fortuna occasionally introduced herself to random students as a SePAS worker – to take away an initial fear of contact from students. The SePAS office where Fortuna worked was located outside the main school building behind the school’s media and music room, so students who want to make use of the resource are not exposed to the public. This was similar in the case of Olivia’s and Bellamy’s school layouts.

The Reality of Public School’s Mental Health Resources

SePAS consultations are usually scheduled during non-class hours to avoid disruption, although students can drop in anytime. The consultation session begins with basic assessment, like checking if the student is eating and sleeping well, before diving into more personal and complex issues. The meeting, which lasts up to 45 minutes, is a crucial step in building trust. After the session, students can decide if they come back or not, highlighting self-determination as central to SePAS work.

To emphasize is that no information that a student confides in a SePAS worker will be revealed to people outside their team, as long as the student is not in immediate danger or the student has not explicitly given their approval. The SePAS thus has a deep knowledge of the school system, is woven into the school apparatus, e.g. a the SePAS is present at each conseil de classe, and thus can give unique support to students. If students want to, parents can also join their children’s sessions with the SePAS – and parents can also reach out independently to the SePAS if they have questions themselves.

Even though queer students still face significant challenges, Fortuna remains hopeful. “There is still a stigma but I think things are slowly changing. People are starting to take mental health more seriously.”

Photo: Giulia Thinnes