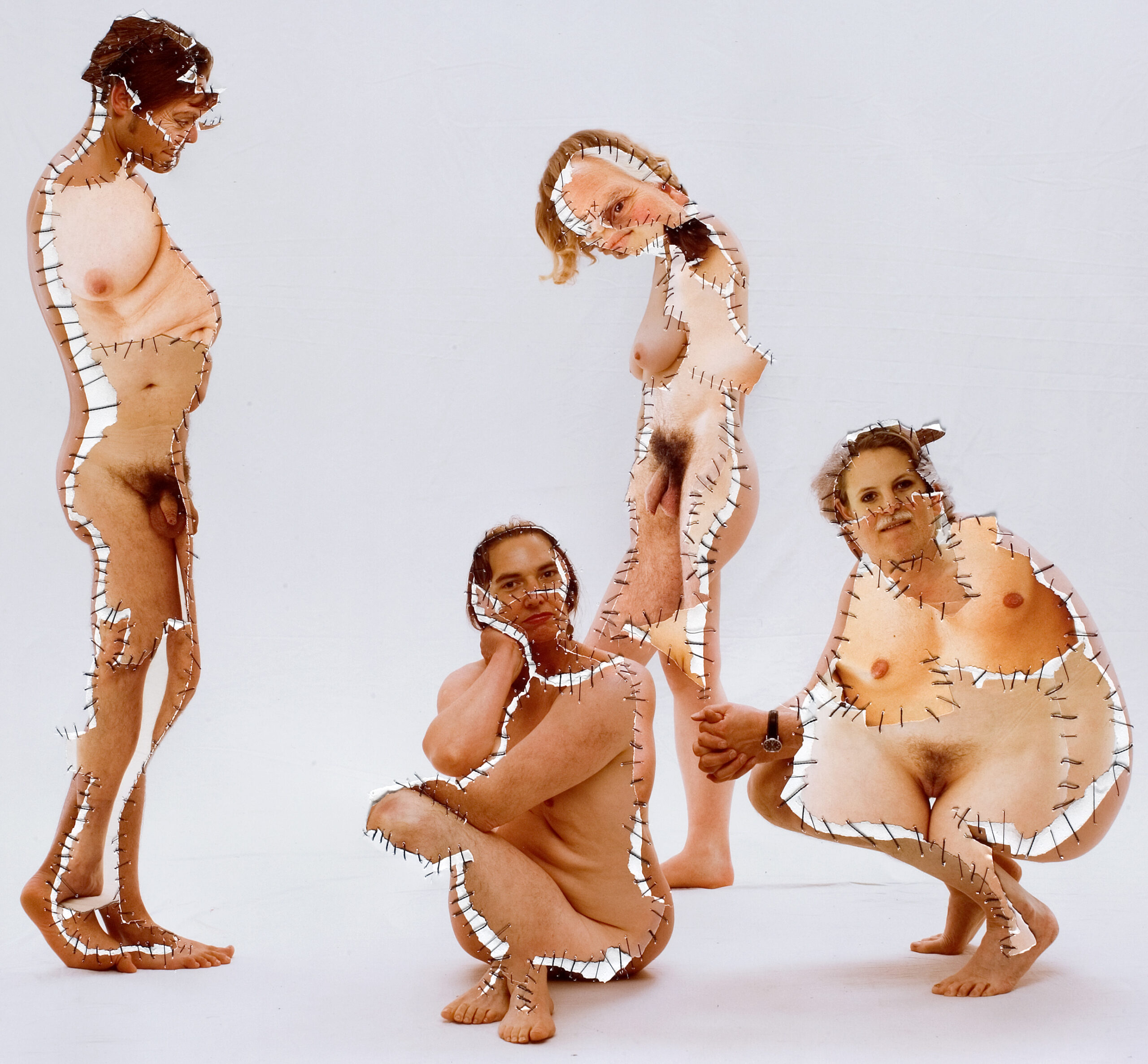

Ausstellungsansicht „Unzensiert. Annegret Soltau – Eine Retrospektive“, Foto: Städel Museum – Norbert Miguletz

In the middle of Frankfurt am Main, the Städel Museum has opened its long-anticipated retrospective Uncensored: Annegret Soltau—A Retrospective (8 May – 17 August 2025, curated by Svenja Grosser), a sweeping tribute to one of Germany’s most uncompromising feminist voices. Featuring more than eighty works spanning over five decades, this exhibition offers a tactile, unsettling, and deeply resonant visual language that positions together questions of identity, memory, and transformation. This retrospective is not just a chance to discover Soltau’s work—it is a rare encounter to witness a body of art that challenges how we picture ourselves—inside and out, and whose themes strike right at the core of contemporary queer and feminist experience.

Born in Lüneburg in 1946, Soltau has always used the body as a battleground and a canvas. Best known for her signature technique of sewing black thread into photographic prints. She is best known for creating viscerally fragmented images of herself, often her face bound tightly with string, producing a jarring yet magnetic confrontation with selfhood. These stitched portraits do not merely disturb; they demand a reckoning, enacting the pressures of societal roles and personal trauma on the very skin. Her early series Selbst (Self) is particularly emblematic: eyes partially covered, lips sealed, flesh distorted, thread-like scars. It’s not a metaphor stretched thin—it’s both wound and suture.

But Soltau’s work does not remain on the surface level. In Vatersuche (Father Search), she documents her personal quest to uncover the identity of the father she never knew—an anonymous WWII soldier—by literally sewing together fragments of official documents, bureaucratic letters, and family records into her own image. The result is a stunning and intimate meditation on inheritance, silence, and absence, one that echoes throughout cultures marked by postwar trauma. Yet this is not nostalgia or melancholy—it is confrontation. Her approach insists that we trace our lineage not only through blood or biology, but through what was hidden, denied, and cut away.

Other series, such as Generativ, follow this thread of intergenerational tension and empathy, merging portraits of Soltau with her daughter, mother, and grandmother. In these hybrid faces, the past bleeds into the present, and the future into the past. Each face is a constellation of women, stitched across time, questioning what parts of ourselves are inherited and what are invented. The body is not a stable archive—it shifts, collapses, rebuilds. Identity, as Soltau seems to say, is an intergenerational patchwork we wear without knowing how it fits.

What makes this retrospective particularly compelling for queer audiences is the way it dissects and reassembles the notion of identity itself. In Female & Trans Hybrids, Soltau experiments with digital manipulation, creating composite bodies that resist fixed categories. These portraits—part self, part other—exist somewhere in between genders, histories, and technologies. Neither fully woman nor man, neither past nor future, these figures flicker between realities: what if our bodies were not truths but possibilities? In a time where gender binaries are being publicly challenged, legislated against, and liberated anew, Soltau’s hybrids resonate as precursors to the kind of fluid, embodied thinking that queerness demands. Hers is not a didactic feminism, but an elastic, experimental one—open to the shifting, stitched realities of lived experience.

Her use of sewing—traditionally coded as feminine, domestic labor—is particularly powerful. She weaponizes it, reclaims it, but also doesn’t fully disown its origins. The act of sewing becomes both violent and tender, an action of care and constraint. The tension is never resolved. Her works feel at home in our current queer dialogues—where softness is political, where identity is something constantly bound and unbound by the world around us.

In a time where gender binaries are being publicly challenged, legislated against, and liberated anew, Soltau’s hybrids resonate as precursors to the kind of fluid, embodied thinking that queerness demands.

I think by now, it’s hard to overstate how this work of art resonates with me, and I believe that for anyone willing to travel to Frankfurt to see it, this exhibition offers more than just a trip across the border—it’s an invitation to reflect on the systems that have shaped us. In Luxembourg, where queer visibility has made important strides, yet questions of identity, tradition, family, and gender which remain unchallenged. Soltau’s work holds up a mirror, but one that’s fractured, seamed, and wholly uncensored. It urges us to sit with discomfort, to see the beauty in fragmentation, and to realize that we are always in the process of becoming.

The Städel’s retrospective is not just an exhibition—it is an archive of becoming, a map of ruptures and repairs. In Soltau’s hands, photography, thread, and skin speak a language we may not fully understand, but instinctively feel. She doesn’t offer closure—only the invitation to continue sewing our own presence.