René FET (he/his/him) is a 45-year-old queer trans man, born and raised in Russia. For over ten years, René was a leading activist for LGBT+ rights and one of the organizers of Moscow Pride (2005 – 2015). He took part in over 50 unauthorized protests, endured more than 20 arrests, spent hundreds of hours in jail, survived dozens of violent assaults, and won 4 international cases against the Russian Federation. Due to continuous state persecution, in 2015 René left the country and got refugee status in Luxembourg. He currently works at the Rainbow Center Luxembourg.

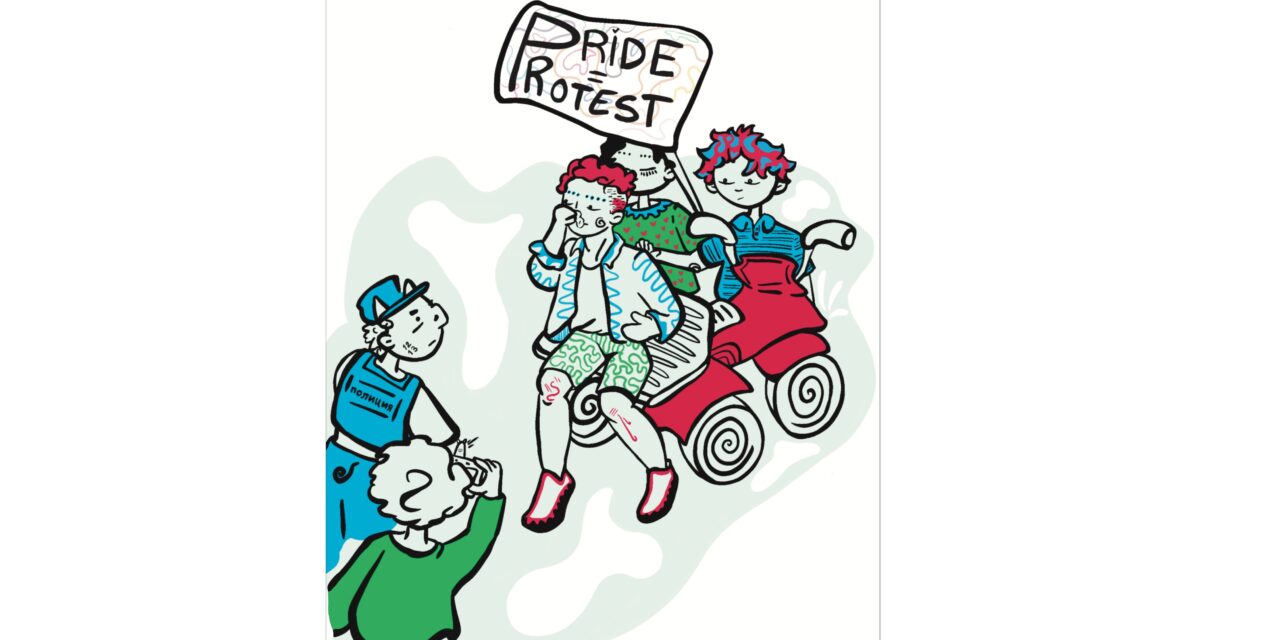

Every year during Pride Month, I feel especially excited. Pride has become an integral part of me. While the debate on the commercialization of Pride events continues in Western countries, and queer activists remind us every year that “Pride is a protest,” this touches me deeply and makes me smile. I know what Pride means and truly is.

My First Pride: Moscow, May 27, 2007

We applied to the Government of Moscow to hold a peaceful demonstration in defense of LGBT+ rights but received a refusal, citing the inability to ensure the safety of participants. We thought the ban was unfounded and constituted a violation of our fundamental right to freedom of peaceful assembly, so we decided to move on with plans anyway.

When I arrived at the Pride venue in central Moscow, the entire area was blocked off by the police. Hundreds of homophobes, policemen, and dozens of journalists had gathered. As soon as anyone in the crowd tried to unfurl a rainbow flag or speak about LGBT+ rights, they were immediately attacked and detained by the police. I saw key leaders, politicians, high-profile supporters, and foreign gay rights activists being detained. I managed to avoid getting caught a few times. For example, notably during the attack and arrest of the well-known British gay rights veteran Peter Tatchell.

Running in circles around Tverskaya Square, I caught a glimpse of a group of activists standing slightly away from the main crowd. These were young girls from the youth human rights project LGBT Rights. I joined them, and we started talking. That’s when journalists began surrounding us and asking questions. Eventually, we made a decisive choice: to march for our Pride. We were equipped with small rainbow flags given to us the previous day at the Moscow Pride press conference and discreetly tucked away in our undergarments and socks. We found ourselves alongside a hippie guy with a flower child flag. Without hesitation, we unfurled our flags and started our march.

Those ten meters were the most impactful moments in my life and the ensuing five minutes were the embodiment of my Pride. We were immediately surrounded by photojournalists. Suddenly, I felt a sharp blow to my shoulder, followed by strikes to my back, to my head… In a matter of moments, my arms were forcibly twisted behind me, as I was thrown into a police van. While we were all detained, our assailants were inexplicably let go. I spent the next twelve hours enduring insults and intimidation at the police station. The next day, I was fired from my job, and my landlady kicked me out of the rented room. Yet, I had never felt so valued, meaningful, and completely confident in the rightness of my cause. That year, the world’s leading news agencies ran extensive coverage of our Pride, with headlines denouncing the violence and brutality that the arrested lesbians and activists had to undergo. There was no mention in local media that the event had never taken place.

This ordeal changed my life, marking a clear “before” and “after”. I realized that I couldn’t come to terms with what was happening. I couldn’t tolerate this injustice, and therefore, I had to say goodbye to my “normal” life. I understood that I would no longer have a stable job, career, material possessions, achievements, or long-term relationships. I saw clearly that no collaboration with the authorities would work — only direct actions would suffice. I was sure that I would come out again and again to demand equality and queer liberation. I was ready to accept myself as an LGBT+ activist, a marginal who had nothing to lose. Because if not I, then who?

Over the next decade, our endeavors to organize the Moscow Pride were met with the same scenario. We went out for unauthorized protests, were attacked, arrested, and subjected to bullying and torture. The Moscow Pride became a battleground where the victims were a few brave queer activists, mostly young people, who just sought to unfurl rainbow flags amidst hundreds of anti-gay protesters, encompassing skinheads, football hooligans, fascists, neo-nazis, and ultra-Orthodox fanatics.

The Moscow Pride wasn’t even a protest because our Pride usually lasted only a few minutes. We didn’t even have a chance to “protest” before we were attacked, kicked by haters, and then brutally arrested and detained by police. However, our assailants enjoyed impunity under the state-endorsed homophobic regime. Year after year, my existence consisted of prolonged detentions in police stations, in jails, in cages, enduring beatings, torture, and humiliation. Such was the reality of my Pride Week.

The Decline of Moscow Pride

With each passing year, there were fewer of us, as fewer activists were willing to sacrifice everything for the cause of queer liberation. Laws grew more draconian, and the persecution of activists more violent. In 2012, Moscow courts enacted a hundred-year ban on gay pride parades; 2013 saw the imposition of the Federal law criminalizing gay propaganda. Many of us sought asylum abroad while others vanished, radically changing themselves and adapting to the political regime.

The last attempt to organize the Moscow Pride took place in 2015, and there were only three of us. We tried to ride a quadricycle along Tverskaya Street, passing the Moscow City Hall, and waving the rainbow flag. But we were swiftly blocked by the police and attacked by anti-gay extremists. By a stroke of fortune, I escaped arrest, but my companions were apprehended and sentenced to ten days in jail.

The era of the Moscow Pride has sunk into oblivion, and now Russia is a fascist totalitarian state in which no freedoms are possible. Long before the war began, we were already marginalized and viewed as enemies of the state. Lesbians, gays, bisexuals, and trans people were set forth as prime targets, hated by the Russians, and persecuted by Putin’s regime. But I still have hope that Ukraine will win soon, that the Moscow regime will be overthrown, and that хуйло (Putin) will go to The Hague, and I hope it will all happen during my lifetime. And I hope one day I will proudly participate in the new era Moscow Pride.

This Job Is Not for Everyone

In Luxembourg, I often hear white cis middle-class straight-passing gays and lesbians say they don’t experience homophobia at all, feel safe, and can easily go out. They also complain that there were more gay bars in the past. They tell me that everything here is perfect: they work, earn money, have a long-term partner, some even kids, a pretty house with a garden (a must), and on Sundays, go to church. Their lives seem good enough, so they say they do not feel the need to disclose their sexual orientation “to everyone” because it’s too personal and may jeopardize their business.

My response to them is the following: You don’t need to explain “it” to anyone, to avoid risking your privileges. You avoid potential conflicts to preserve your comfort because your rights and freedoms were granted, not fought for. Defending rights requires bravery and belief, a job reserved for the intrepid few. This job isn’t for you; this job is for people like me.

People like me have chosen to take risks, to explain, to confront and negotiate, to carve out more and more safe spaces for gays/queers. Through queer art and drag performances, they pushed past their own fears to make queer people visible and share queer culture outside of the closet.

We did this so that people like you can comfortably put their asses on a gay bar’s chair, get drunk, and dance in peace without any fear of being insulted, robbed, beaten, raped, and thrown out on the street, where cops would pick them up, take them to a police station, and torture them until the morning. So that people like you can proudly wear rainbow laces once a year and spout your “unique” knowledge about Luxembourg as a “queer-safe haven”, free from discrimination of all kinds.

Even to this day in Luxembourg, opening a gay bar or securing a venue for a queer party serves as an act of queer activism. Despite maintaining unwavering professionalism, adherence to protocol, and financial accountability, telling the truth might get suddenly rejected by a venue owner without any reason. This is the price we pay for queer visibility.

How My LGBT+ Activism Began

I was born and grew up in a small town in the south of Russia. From an early age, I felt different and told my parents I was a boy. But they rejected me as a male child and pushed me to follow gender standards. Soviet Union society and a provincial school did their job to break my feelings about my identity and forced me to fit inside the cis-heteronormative box.

I refused to hide my queerness and proudly tried to be my true self. Feeling deeply gay and presenting masculinity, I was always gender non-conforming. People saw me not as a woman, not as a man, but as a freak, and were aggressive toward me. I was often insulted, and beaten on the streets, just because I looked “not normal”, androgynous, punk, or alternative. Because of my extra short hair, no hair, green hair, visible tattoos, too many tattoos, too many piercings, wrong-side piercings, a rainbow bracelet, leather bracelet, pink shorts, wrong-color shorts, gay-sign t-shirt, American-flag t-shirt – wearing this meant I looked gay (like пидар, a fag). Therefore, I was a subject of systematic discrimination, harassment, and physical violence — just for expressing myself. Through this direct violence, I learned to survive, to be brave, to protect myself on the streets, to resist, and to bash back.

After finishing high school, I sought out bigger cities, searching for a safe space and “my own people”. And I found them in gay bars and clubs, where I began working. I felt I was in the right place, like at home, but stronger and more capable. For many years, I was a bartender and then a manager, a security guard, and then a “door bitch”/face-control, deciding who is allowed to enter. I watched over queer folks ensuring their safety. After all, I knew how to react to threats because I experienced all that shit firsthand having lived my life as an openly queer person.

In the early 2000s, I moved from one city to another, working in different gay clubs. In every corner of the country, I witnessed anti-queer violence. I remember fighting off haters attacking clubs, bent on destroying everything and everyone inside. I remember driving away muggers lying in wait to rob lonely, drunk gay men leaving clubs. I recall telling off dirty taxi drivers who preyed on intoxicated lesbians, aiming to take advantage of them and show them what “real men” could do to “cure” them of their lesbianism. I remember hiding young drag queens from nasty cops who wanted to abduct them and gangrape them at the precinct. And I shall never forget the memory of assisting nightclub security in removing my dark-skinned friend’s lifeless body from the noose; hours before, this friend admitted to me about not feeling comfortable with their assigned male gender and longed to start a medical male-to-female transition.

During those years, it seemed normal to harass queer people and silence them. But for me, it was anything but normal — it was unfair, sad, and infuriating. I felt outraged. I saw so much queer blood spilled, broken fingers, smashed noses, heads, and stab wounds… I shed my own blood, protecting queer siblings from anti-gay aggressors. I felt I couldn’t stay silent and wanted to speak out. That’s why I decided to join the Moscow Pride. I wanted to fight back against queerphobia on a larger scale. That’s how my queer activism began.

And Pride in Europe: Too Corporate?

The origins of Pride can be traced back to the 1969 Stonewall Riots, led by a group of marginalized queers in New York City. From a street protest demanding gay liberation, this movement has grown over the years to become a carnival of jubilation. And here, in the bastion of the Western world, we witness the explicit backing of large corporations that created their Pride rainbow collection, and most people see Pride as a time to get drunk and dance the day away with friends. The meaning of Pride has shifted to a sales pitch and a party — What has Pride become?

I remember my first “real” Pride Parade in Brussels. I was so impressed by this huge street fête and saw so many different people come together. Gay parents with kids marched alongside fancy drag queens, half-naked twinks in “boas with feathers in the ass” with leathermen and puppies, and politicians close to funny furries. I thought, “Oh boy, that’s so amazing, fuck it! Fuck the fight, I wanna celebrate! And yes, finally I can buy and wear my rainbow Converse without any fear of being beaten for the gay sign.”

And yes, at my first Pride, I was drunk and danced the night away, feeling free, and accepted… considering that all these small things might be so important for someone who is not allowed to do them in their everyday life. I thought there were so many things to celebrate: from legal rights to equal marriage to the everyday existence and expression of our identity. I thought it was all done — gay rights are human rights, and all queers are liberated. I thought I was such a “wild” Russian LGBT+ activist, just out of the Moscow Pride street fights, like a Neanderthal with a baton out of a cave. I thought, what’s next? There seemed to be no place for queer activism in Europe anymore…

The Outgoing Fight

But very quickly, I learned that our fight was far from over. Trans people are still pathologized and forced to undergo sterilization. Intersex identities are not well recognized and not visible at all. Intersex kids undergo unnecessary genital operations. Gay couples are restricted in parental rights. Conversion therapy is still not prohibited. Sex workers are stigmatized and cut off from healthcare. Trans migrants have no access to legal gender recognition. Kinksters are unfairly excluded from several Pride celebrations…

Even in places where Pride seems like a party, there are undercurrents of discrimination and inequality. Beneath the surface of rainbow flags and festive parades, there are still struggles, battles, and victories yet to be won. Especially at a time when rainbow identities are increasingly under pressure internationally and people are losing freedoms, the essence of Pride, as a protest and a fight for rights, is as relevant as ever.

In Luxembourg, while the LGBTIQ+ community enjoys significant freedoms and protections compared to other places, there are still instances of discrimination and bias. Queer people of color, queer refugees, trans individuals, and those from less privileged backgrounds often face unique challenges. These struggles are not always visible during the celebratory aspects of Pride, but they are very real and demand our attention and action.

Pride Is Personal

For me, Pride is deeply personal. It reflects my journey, my struggles, and my victories. It is a tribute to the brave individuals who fought before me and a call to continue that battle for those who come next. Pride is not just a moment in time; it is a history, a rebellion, a movement, a lesson, a show, a demonstration, and a celebration of our collective strength, resilience, and diversity at its finest.

Pride is still a protest, and I am proud to be a part of it. Seek me out at your local Pride, I’ll be representing those marginalized groups and I’ll be marching on behalf of those who can’t.

Illustration: Liou